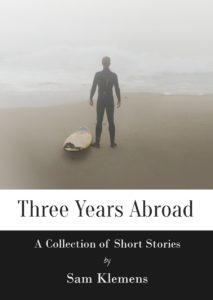

This story is part of a collection from my first self-published book, Three Years Abroad. It’s available on Amazon for $8.99 and if you have Prime then the shipping is free. I’d be thrilled if you wanted to pick up a copy. You’ll get this story and others like it, printed up and delivered to your door. Until then, please enjoy the story.

This story is part of a collection from my first self-published book, Three Years Abroad. It’s available on Amazon for $8.99 and if you have Prime then the shipping is free. I’d be thrilled if you wanted to pick up a copy. You’ll get this story and others like it, printed up and delivered to your door. Until then, please enjoy the story.

***

“If you don’t know where you are going any road can take you there,” said The Cheshire Cat. I didn’t know where I was going so I went to Kochi. I stayed a month, it rained every day, then I went to New Delhi because it was cheaper than flying to Mumbai. My motivation in visiting India was two-fold. In the first case I had romantic ideals of the country, mostly from reading Shantaram. I thought that if I went I might meet my own offbeat Indian guide who would show me the real India. I would fall in love with a beautiful woman and when she refused my advances I’d lose myself in a string of opium dens only to be rescued by a charismatic zealot who would give me a horse, a rifle and a reason to live. I would look up to this man as a father, ride with him to Afghanistan and there we would fight a holy war whose origins dated back a thousand years. Or something like that.

Should this fail to materialize I had a secondary motivation. By eighteen I had in mind five things that I’d like to do with my life. By twenty-six I’d done four of the five, the last on that list was a motorcycle trip in India. To finish the list I had to find a bike. It took me two days. A rental shop the size of a bathroom on the second floor of an industrial complex in downtown New Delhi. The man who rented me the bike had a limp handshake and acted as though we’d known each other for years. The papers I signed said that if anything happened I was responsible and the $200 deposit I left supposedly guaranteed that I’d bring it back. Once the paperwork was in order I was given the keys and set loose on the streets of New Delhi. The ability to operate the bike was taken for granted.

By this time I was aware that everything I knew about driving was wrong. In India things are done differently. Most intersections don’t have a stop sign. Each driver approaches the crossroads and attempts to get through it without stopping. The losing driver, stewing in his cowardice, is the one who stops in order to avoid the accident.

Turn signals are optional. Some drivers will use them when they’re attempting a dramatic maneuver, like crossing four lanes of traffic in six seconds, while others never bother with them. You get the feeling that most car owners, were the turn signal stick to fall off, would not have it replaced. In lieu of signals and courtesy the Indian driver applies the horn. This warns other motorists of your presence and the effect is similar to a bat and his echolocation. A driver who fails to signal his presence with a blast of the horn is liable to be driven into.

Naturally the horn system is infallible and accidents happen. Not as many fatal accidents as one would suspect, looking at the exquisite insanity of the Indian road system, but small ones are common. Automobiles graze each other at walking speeds and the drivers don’t even get out to check the damage. It’s common to see cars with hundreds of scratches and gouges at bumper height. Indian drivers seem to be resigned to this, even the most conscientious driver will be the victim of scrape-and-runs if he does anything other than leave his car in the garage. The thought of driving a Rolls Royce through downtown New Delhi inspires the same feeling as hanging the Mona Lisa in a college dorm.

While teenage Sam hadn’t realized that driving in India was the real life equivalent of Grand Theft Auto, twenty-something Sam didn’t think this justified bailing on ambition. However, concessions were made. Instead of going to the Himalayan mountains, I would instead go to Agra, home city of the Taj Mahal and a mere one-hundred and twenty miles from downtown New Delhi. My bike was a Baja Avenger 220, the cruise edition, and my baggage was my backpack with a few days of clothes, two liters of waters, my laptop, crackers, two charged batteries for my phone and an appreciation of the absurd. I was wearing a lambskin jacked I’d bought special for the trip and in the pocket there was my phone, loaded up with Google Maps and Post Malone.

This setup worked well and on the morning of my departure it took me only an hour to reach the outskirts of New Delhi, a barren place overrun with uninhabited fifty-story apartment buildings, power plants and empty stadiums. It was ninety-five degrees and sunny, a beautiful day for riding. I covered thirty miles and as the buildings gave way to fields my confidence grew. The highway was three lanes wide, only a light spattering of traffic and I hit the throttle till I was doing forty. The countryside was a blur, for forty is quite fast in India where a 600cc bike is considered massive, when I drove over a screw.

The rear tire popped and the back of the bike started to flop like a landed fish. This terrifying sensation was so unexpected it took me several seconds to take proper action. Ease on the front brake, hold the handlebars straight, put down my legs to keep the bike balanced. Fifty feet later I was at a dead stop. My heart was working overtime and my body electrified with adrenaline. My hands were shaking, my breathing shallow and I felt lucky to have not left my skin on the road. I shut down the bike, took off my helmet and looked around. What I saw hit me twice as hard as the almost-accident I’d just survived.

The highway was built on an embankment and afforded a view over the surrounding flatland. Down the slope and parallel to the highway ran a dirt road. A dust cloud followed a man sitting on a wooden cart whipping a donkey. In the distance a half dozen farmers worked a pale green field which, to my untrained eye, looked inhospitable to vegetation. Further down the road three kids rode bicycles and shouted in Hindi. Of everything I saw, nothing suggested that the industrial revolution had reached where I was now stranded. Cold fear gripped me and I felt sick to my stomach. That moment, as the gravity of my situation sunk in, was the most alone I’d ever felt in my life.

I called the rental shop and was told to call a different number. I called that number and was given a different number. I called that number and the man said he didn’t know anyone that far out of New Delhi who could help. He kindly reminded me that per our agreement it was my responsibility to deal with burst tires and suggested I try talking to people. I hung up. If I waited by the side of the road I would wait until I died. I wrapped up my headphones, left my backpack by the bike and squeezed under the barbed wire fence. There was a road fifty feet away and I walked towards it. The upside to my situation, I reminded myself, was that most people in India speak English. Occasionally their accents are so fantastic that it’s impossible to understand what they’re saying but at least they can understand you. Down the road I only walked a hundred feet before a man on a motorcycle made eye contact with me and, as I was possibly the first foreigner to ever set foot on that desolate road since the time of Buddha, he stopped his bike to stare at me. I waved him over.

“Hello,” I said.

“Hello. How are you?” He asked.

Overwhelmed and frightened, angry that my bike had failed after only an hour of driving, I replied dishonestly, “I’m fine. How are you?”

“Oh things are going well, very well. Why are you here?”

I pointed at my bike, just visible on the highway above us. “Punctured tire. Do you know where I can get it fixed?”

The man on the motorcycle said something in Hindi to the guy sitting behind him who nodded. He turned back to me. “Yes, OK. Get on.”

“Where, here?” I asked, gesturing at the gas tank.

“No, there,” he replied, pointing at the back. His passenger scooted forward, I got on the last three inches of the bike and the three of us drove down the dirt road, through a dusty field to a small town where the most imposing building was two stories and made of concrete. We stopped to admire a hand-driven water pump.

“The best water in India,” my driver claimed, before we continued.

We passed naked children and dozens of buildings made from straw and mud. The mechanic had a garage at the end of town and didn’t seem surprised to see us. He was working on another motorcycle and shouted at my driver in Hindi who translated for me.

“He will be done soon. We can wait.”

“OK, that’s fine.” I looked around at the village which was really just a row of houses along the main drag. “Do you live here?” I asked.

“I grew up here but I live in New Delhi now. I visiting my parents this weekend.”

“Cool. What do you do in Delhi?”

“I play professional cricket,” he replied.

“Are you good?”

He smiled, “I very good. You come see me to play sometime.”

“Sure, why not,” I said. The situation was so surreal that I would have nodded and agreed if he’d asked me to be the honorary ambassador to Ecuador.

The mechanic finished his work and we drove back to my bike where in twenty minutes he took the back wheel off, pulled the screw out of the tire with pliers, patched the hole in the tube and put the whole thing back together. It cost $8 and although I was sure that I’d been had I gave him $10. I thanked my driver, we took a selfie and then I put on my leather jacket helmet and music and accelerated through the gears feeling very cocky. I’d been put into an unenviable situation, kicked the shit out of it and now I was off again, hardly an hour after I’d come to an unplanned stop. I made it ten miles.

The second time my back tire blew out was so unexpected it hit me like a teenager texting and driving. While I managed to wrestle the bike to the side of the road unharmed I did not escape unscathed, emotionally a toll was collected. For an unknown reason the second blowout sent a wave of terror through my brain where it became lodged. In one second an unbreakable association was formed between motorcycles and death and no amount of further introspection has ever successfully fixed it. And why should it? The connection is logical. It was as though my last five years of riding I had been blissfully ignorant and then after the second blowout I finally woke up to the truth, a motorcycle can kill you. I felt shell shocked and incapable of action. I sat down and looked out at the brown empty fields.

That I was so mentally impaired was not so good. I was still on the side of a highway in rural India, halfway between New Delhi and Agra, and I had nobody to call. I wish I’d never done this, I thought. I would give anything to just be a normal person who wouldn’t even consider doing this type of stupid shit. Why am I fucking like this? When this speculation failed to lead to a solution I decided the only thing to do was get on with it.

My immediate concern was the disturbing déjà vu of finding myself, again, on the side of the highway next to a dirt road without a town in sight. This time, however, there was no man with a donkey or friendly local on a motorcycle. Just empty fields and far off in the distance a row of mud huts. I put my helmet and bag on the bike, slid under the barbed wire fence and walked to the road just as a man was driving past. I waved at him but he shook his head and kept driving. I walked further and came to an underpass where two kids on bikes were talking to a pair of homeless men sitting on a tarp. They were unshaven and passing back and forth a jug.

“Hello,” I said to all four of them as I approached. They stopped talking and stared, they looked at me like I was the Prime Minister of India. What the hell, they must have been wondering, was a white foreigner doing under their bridge? I addressed the two homeless men first as I thought they might speak better English. “I had a tire puncture, is there a mechanic here?”

I might have had better luck speaking Mandarin. I tried a different approach. “Motorcycle, tire puncture.” I spoke slowly and tapped the back tire of one of the boy’s bikes. Both of the boys faces lit up.

“Tire puncture!” They said together, repeating it several times. “Mechanic, yes?”

“Yes,” I nodded. “Where. Is. Town?”

They ignored me and talked quickly in Hindi. The homeless men, who had been silent, joined in the conversation. This lasted thirty seconds then the taller of the two boys spoke. “I go town.”

“Awesome, thanks,” I replied. Selfishly I’d hoped one of them might make that offer, it wasn’t one I was planning to turn down. “I will wait here.”

“What?”

“OK!” I said with a smile and gave a thumbs up sign. He took off towards town. The homeless men cleared a place on their mat and I sat down. The conversation was limited as I didn’t know Hindi and their English was no better but when I took out my phone they were fascinated. They looked at it, pointed and said things I didn’t understand. I held it out but they wouldn’t touch it. The kid sat on his bicycle and gave me candy and used every word of English he knew which was very few.

The boy who’d gone to town came back after twenty minutes sweaty and satisfied and five minutes later the mechanic arrived on a beat up Enfield. In fifteen minutes he replaced the tube instead of patching it and I felt much better about my chances of making it to Agra. I thanked him the way I thought he might like best, with money, then I started the bike and everyone waved as I drove away.

The second blowout hadn’t rattled my nerves it had broken them. I was now jumpy and unhappy. Every few minutes I thought the tire was going to explode so that in the next couple of hours, twenty or thirty times I brought the bike to a stop on the side of the road. Before I could start again I had to slap my helmet like a quarterback psyching himself up for a third and tenth, then scream like a Celtic warrior going into battle. Only then did I get back on the road and rarely for more than a few miles. It took me four hours to drive forty miles.

By the time I reached Agra the sun was low in the sky and a routine three hour trip had taken me nine. I had made it though by God! My phone took me to within a block of my house where I could take a shower, eat dinner then take as much sleep as my body would allow. After one-hundred and twenty miles the last stretch should have been easy, just find the narrow alley marked with the blue sign, drive a hundred feet and shut off the bike because I’d arrived. Instead, I drove into a slum. Pigs rooting in silver-colored sewage that ran in six inch channels in front of the patchwork homes and piles of garbage burning gray sulfur smoke. It had taken only three wrong turns and I was engulfed in a poverty which would make any American trailer park look like a gated Malibu community. How had I angered Krishna enough to deserve this?

I drove in shapes for twenty minutes. When I passed the same noxious pig barn for a third time I was forced to admit I was lost. I shut off the bike and considered giving up on life. Whatever the world was planning to force upon me, it could be no worse than what I’d already done to myself. Laying down to die had its merits but I thought I had at least one more chance. I put the bike on its stand, walked up to a gaggle of kids and asked them how to get out. They laughed at me being there and told me in surprisingly good English to take this left and that right and when I followed their advice I found the main road in three minutes flat. An hour later I was having dinner at a rooftop restaurant watching the sun set over the Taj Mahal.

***

The highway I’d taken to Agra was different than what you’d find in America. Every mile or two was a pile of broken automobile glass, usually on the shoulder, sometimes well into the lane. That cleaning up these piles of glass might be an inexpensive way to improve the safety of their highways has apparently not occurred to anyone in India.

About half of the tolls, for reasons unclear to me, were only for cars. The bikes drove onto the dirt shoulder in order to avoid paying. There was no speed limit and if there were police they never showed any concern about the behavior of motorists. Barbed wire ran the length of the highway, from Agra to Delhi, and its purpose was to keep animals off the highway as well as stop people from using the road without paying. A fallible system, near the end of my drive I’d stopped to help two men pick up a motorcycle and shove it over the fence.

My reason for going to Agra had been to visit the Taj Mahal. On the morning after my trip from hell I walked to the entrance gate and read the sign. A ticket for Indians was 40 Rupees and a ticket for foreigners was 1,000. The thought of submitting to this injustice was inconceivable. On the principle that I had come to dislike India and refused to give them my money, I chose not to pay. Instead I had lunch on top of a tall hotel and enjoyed the Taj remotely.

After lunch I returned to my room and passed the day in a state of anxiety, nervous at having to once again drive the bike. I speculated about the feasibility of paying someone with a truck to drive me and the bike back to New Delhi but I had no way to set this up and I thought it would cost more than I could afford. Abandoning the bike in Agra, taking a bus back to New Delhi and leaving India on the next flight out also appeared as an option, but an unwise one at that. I was going to have to drive back.

The morning of my departure I ate toast with strawberry jam, a banana and black coffee. A fast shower then I sat cross legged on my bed and made a deal with the universe. If you just let me get back to Delhi safe, I promise I will never again rent a motorcycle in a third world country.

When I tried to start the bike the battery was dead. Two men pushed me till the engine turned over and exhaust shot out the back. I thanked them, drove to the gas station and then got onto the highway. I drove for an hour and then violently slammed my feet into the ground to keep from falling over. For those of you counting, it was the third time the rear tire had blown out. My hands were steady my pulse at resting rate. I had expected to be betrayed. At this point cursing the bike would have been like getting angry at a crying baby. My only wish, as I pushed that wretched son of a bitch onto the shoulder, was that soon it would be dismantled by indolent teenagers, melted down and made into a septic tank.

While I had grown accustomed to getting tires fixed in odd places, this time when I looked at the countryside I didn’t see anybody on the dirt roads or in the fields that stretched for acres by the dozen. There was no overpass with men sleeping under it. My best choice was a rest stop two miles away. I put the bike into first gear and it ran perfectly at walking speed while I walked next to it, my right arm stretched across the gas tank to reach the throttle and the flat tire going thwack thwack thwack on the pavement. It was a cloudless ninety-nine degrees and the sweat poured off so it looked like I’d been rained on. When I had just a quarter mile to go I had to stop and rest in the shade, so strong was the feeling that heat stroke was imminent. I rested for ten minutes, almost but for some reason didn’t puke, drank the last of my water then stood up and finished the walk at a brisk pace. Pushing the bike two miles had taken fifty minutes and in that time no person had stopped to see if I needed help.

At the tire repair shop I poured water over myself and lay sprawled on a filthy couch while three incompetent adolescents removed the rear tire and replaced the tube. Without confidence they reassembled the bike by trying parts in one position and then another. When the head mechanic finished he took the bike off its stand and asked me for more money.

“I want 800,” he said.

“We said 600! You agreed to that before,” I replied angrily.

“Yes but there are three of us, we need more money!”

I looked at the three guys. One had done all the work, another had watched and the third had gone to the pharmacy and gotten prescription pills which I doubted he had a prescription for. We were quibbling over $3, more money than the average Indian worker will earn in a day, but it was the principle God dammit! We stared at each other. He won. I handed over the money, walked over to the convenience store and drank a liter of water then got back on the bike which was hotter than a vinyl car seat in August. I felt good about the prospect of making it back. I saw it as highly unlikely that the tire would go flat again. Four tire blowouts in two-hundred and forty miles seemed improbable, even on the glass strewn highway. You chose this shit, nobody forced it on you, I reminded myself as if it made anything better. Then I started the bike and drove fifteen miles an hour until I got to my apartment in New Delhi seven hours later.

I was so dehydrated that I had a freshman’s hangover the next day but it didn’t matter, I had completed a motorcycle trip in India and with mixed feelings I realized that at twenty-six I had now done everything teenage Sam had ever hoped to achieve. A motorcycle trip in India, the final strike on the list that ended my adolescent dreaming.

***

The home I returned to in New Delhi was a single large room that had a balcony and air conditioning. My landlord described the neighborhood as posh although down the road was the burnt shell of a car and past that a public toilet you could smell from thirty feet. Next to the toilet a man sat on the sidewalk with his scissors barber’s chair and a torn robe. He would cut your hair for fifty cents or give you a shave for thirty. Other men had restaurants on the sidewalk and after you finished eating they’d slosh your dishes in tepid water and then somebody else would use them. I ate at such establishments often.

When I took a taxi and we stopped at intersections it was not unusual for beggars to tap on the windows, holding their hands out for money. Some beggars were women or transsexual men, it was difficult to tell which, done up in garish makeup. Others were waifish girls of eight or ten carrying infants on their shoulders. Their faces smeared with dirt, they made scooping motions with their hands that terminated at their mouths. If you gave money they yelled out and other children would come so that two or three sets of hands were reaching through the window and you felt overwhelmed and sad and wanted the light to change so that you could drive away and not have to think about it anymore.

People dumped their rubbish wherever was convenient. A man on the street in front of me was surprised when a bag of garbage landed on his head, a woman from a second story apartment had carelessly dropped it on him. The dropped garbage ended up in piles and the piles ended up in the water. The water in India was, in every case I saw, polluted black as Hitler’s soul. There was trash on the banks, stuck against concrete bulwarks and floating around in eddies. Sometimes I couldn’t smell the water and other times it reeked like capitalism’s hangover. Oily sewage the color of mercury ran in crevices between buildings and drained into rivers and canals.

It wasn’t the first time that I’d visited a poor country, Cambodia especially was polluted dirty and impoverished. However, India threw everything in my face with a previously unknown intensity. On a five minute walk in downtown New Delhi you could pass an outdoor toilet, begging children, piles of trash, a group of men who would unabashedly stare at you, every minute a horn blast so loud you wished you had ear plugs, water so foul it couldn’t technically be called water and then as you were about to walk in your front door some crazed maniac would come within inches of running you over. Also, it was one-hundred and two degrees so that any walk, even down the block to the bakery, meant sweating through your shirt. On this point, however, I reasoned it was still better than dealing with snow.

The highlight was the food which was, almost without exception, delicious. When I arrived in India I had no clue what any of the dishes were. As the menus rarely offered a description I would ask for something not spicy, the waiter would point at a name I didn’t know and I’d order it. If it was good I’d remember what he pointed at. Chicken mughlai, mutton shahi korma and butter chicken were my favorite dishes and I ate them with parotta and raita.

I have a friend, the smartest man I know, who enjoyed his time in India and I asked him why. He said he, “liked that everyone is sharing in the experience with each other.” I thought this a fine way of putting it. India is a tough country that’s ludicrously hot, overcrowded and extremely poor. People struggle daily to eat and the safety net is death. Yet the struggle is shared and anyone can turn his head and see millions of others living no better or worse than himself. It’s the bleeding edge, water splashed over crusty eyes, the illusion shattering truth of what life is like on the precipice.

“Curiouser and curiouser!” cried Alice.

***

Like this story? Want to read more like it? My first self-published book, Three Years Abroad, is now available on Amazon. It’s 10 short stories, including this one, about my time abroad, the people I met and the interesting situations I found myself in. It’s only $8.99 and if you have Prime then shipping is free. I’d love it if you want to pick up a copy. All proceeds will fund future adventures in off the map countries.

This story is part of a collection from my first self-published book, Three Years Abroad. It’s available on Amazon for $8.99 and if you have Prime then the shipping is free. I’d be thrilled if you wanted to pick up a copy. You’ll get this story and others like it, printed up and delivered to your door. Until then, please enjoy the story.

This story is part of a collection from my first self-published book, Three Years Abroad. It’s available on Amazon for $8.99 and if you have Prime then the shipping is free. I’d be thrilled if you wanted to pick up a copy. You’ll get this story and others like it, printed up and delivered to your door. Until then, please enjoy the story.